Buzz and Colonel Toad #1 was one of a small stack of 25-cent comics I picked up from a discount bin at some store somewhere several years back. I'm pretty sure a second issue of the series was published, but I've never seen it anywhere except online, so all I have is the debut. That's fine, though, since it's a self-contained story. It's a black-and-white children's comic from 1997, or at any rate I assume it was targeted at kids based on the simplicity of the language and characters. Also because it seems to want to have a moral, a valuable lesson to impart on its younger readers, though I'm not sure how well that succeeds. Partly because the whole issue is loosely put together, and partly because the underlying message is questionable at best.

I do appreciate the way this story begins, because it wastes no time with introductions. For a kids' book especially, this feels unusual, so I give writer Phil van Steenburgh credit for diving right into his bizarre setting and cast. This is a period piece of sorts, except I'm not entirely clear what period it's aping. Modern technology doesn't exist, but there are things like planes and cars, so...less than 100 years ago, say. Also animals and humans interact as equals, which is more important than the era. As their names suggest, Buzz is a bumblebee, about the size of a dog but with human intelligence and speech. Colonel Toad is a man-sized and well-dressed toad, who I guess is also literally a current or former colonel in whatever military exists, though the details of his record are not divulged here*.

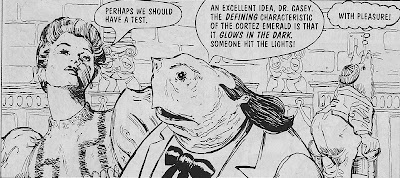

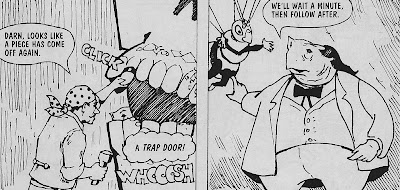

There's no time for that kind of backstory, because right on the opening page, Buzz is running late. He's headed to see Colonel Toad donate a one-of-a-kind emerald to the local museum, supposedly the last relic of the ancient Cortez culture. But before Toad can finish presenting his gift, two other citizens emerge from the crowd with their own Cortez emeralds. All three pass the glow-in-the-dark test, which should be impossible, and Toad thinks the whole affair seems suspicious. Without missing a beat, he and Buzz leap into a plane and fly off to the island where the Cortez lived before the earthquake that supposedly ended their civilization. Once they arrive, the heroes are greeted by a manic tour guide/restaurant owner who hurriedly shuffles them to a few unimpressive sights before forcing them to eat bad sandwiches.

That tour guide is the story's villain, Gigi the Gypsy. It's pretty offensive, there's no doubt, that the bad guy is a gypsy dealing in illegal emeralds, and that's not the only culturally insensitive part of the story. Gigi's crime is based on the discovery that the Cortez were still alive and thriving in a hidden underground valley. They've also continued to mine emeralds all this time, so when Gigi finds them, he uses modern drugs to position himself as medicine man and therefore be in charge. He then abuses his power to sell the emeralds back home, until Buzz and Toad show up and foil his plot. Gigi is definitely exploiting the Cortez and should be stopped, but one of the things Toad most strongly objects to is that the Cortez were denied a chance to interact with modern culture. This doesn't sit very well with me the way it's presented, with a very stark and inconsiderate sense of right and wrong. Nobody asks if integrating the Cortez is actually what's best for anyone, or what they themselves want. Their first contact was with Gigi, and it led to them being lied to and taken advantage of. Why is it necessarily a good idea to move further in that direction, as opposed to allowing them to continue as they were, or even protecting them somehow? Maybe there are sound reasons, this is after all a totally fictional reality of which I've only seen the tiniest fraction, but it would've been nice if they were included, or just if the discussion took place.

There is dialogue at the end of the issue, from Toad's friend Oogles (a fancy worm, see below), stating that the Cortez are getting help adjusting to the world and that they gave Toad an emerald to thank him for what he'd done, so all's well that end's well, I guess. But there's still a gypsy antagonist for no reason other than "gypsy" being inappropriate shorthand for "untrustworthy", and an uncomfortably imperialist tone to the whole narrative.

It's also a story that moves too quickly for its own good. Any new information is stated out loud by the characters, sometimes necessary because the art's unclear, but more often I think van Steenburgh uses the young age of his target audience as an excuse to write a bit lazily. This leads to regular info dumps and moments of handwaving dialogue, corner-cutting that muddles the story in the name of moving more quickly onto the next beat. It also dampens the attempts at humor; this isn't as lighthearted an adventure as I think the creators believe it to be, and the jokes fizzle.

The only section that's slightly funny is the back-up feature starring Oogles. We learn that he's a professional shrew-drawn carriage driver, and I think it's amusing that in a world where giant worms wear top hats and smoke pipes (and have arms, for whatever reason) there would also be big shrews that are basically just horses. What is the logic behind that? To make it even more ridiculous, Oogles later tries to hire chipmunks to replace his shrews, even though the chipmunks can talk and stand up just like he can, so...what is the distinguishing line between which animals behave like humans and which do not? Buzz is somewhere in between, too, by which I really just mean he isn't wearing clothes.

In Oogles' story, he wants to find something to drive other than shrews, and tries a number of different methods of transportation that all fail miserably. Just as rushed as the main story, the back-up actually benefits from the pace, because the rapid-fire succession of Oogles' mistakes is much of what makes them amusing. In the end, he learns (and says) that the grass is always greener on the other side, and decides to return to his shrews. Which, since they're basically pets and therefore a responsibility to which he's already committed himself, is the best lesson for children to learn in this whole comicbook.

The art is by Alan Howell, and it's just as uneven as the writing. It can be very sparse and sketchy, and even the most detailed panels aren't especially full. And it looks like some panels are partially traced from each other, with most of the characters and set pieces in exactly the same position save for one or two minor shifts. This and the not-infrequent blank white backgrounds indicate a lack of effort similar to what's evident in some of the script, deadening the entire work.

So Buzz and Colonel Toad #1 is not a winner, perhaps not worth the quarter I paid for it. I do, however, have one sprinkle of praise to toss out here at the end for Howell's work: I actually laughed when I saw Gigi's giant drill vehicle. It's a dumb plot point, since it never gets used and it's a clichéd visual that doesn't fit in this story whatsoever. But as an image, it's uniquely intricate, and thus an actual surprise, earning it's one panel and then some.

*The back cover does say that Toad's grandfather fought in the Great Swamp Wars. The most intriguing tidbit of the entire issue, I'd say.

No comments:

Post a Comment